|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Egyptian papyri,

including surgical case records from the 17th century B.C., describe bone

lesions, intestinal parasites, dysentery, fatty tumours, vascular aneurysms

and ulcerating masses. The ancient Egyptians also recognised the phenomenon

of blood accumulation within inflamed tissues.

There is, however, scarcely a trace of any pathological

observations made during the dissection and embalming of approximately

700,000,000 human bodies and countless more animal and bird cadavers over

the span of 5000 years of dynastic Egypt.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is a photograph of the world’s oldest suture,

placed by an embalmer in the abdominal skin of a twenty-first dynasty

mummy in c. 1100 B.C. Most embalming wounds were not sutured. Some were

covered with beeswax. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

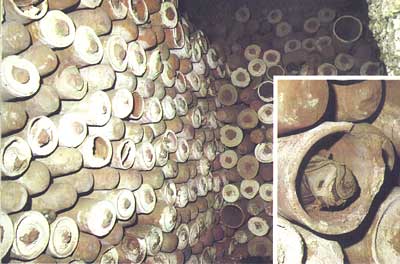

These are thousands of mummified ibis and falcons, sealed in small pottery

sarcophagi and stacked in underground galleries at Saqqara in Lower Egypt.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

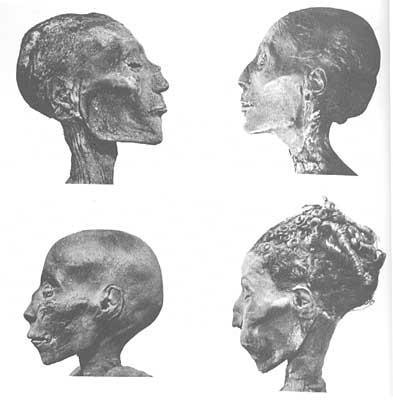

Four of the best mummified royal profiles from ancient

Egypt: Ramses V (top left), Thutmosis IV (top right), Thutmosis I (lower

left) and an unknown lady. They were embalmed between 1550 and 1100 B.C. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

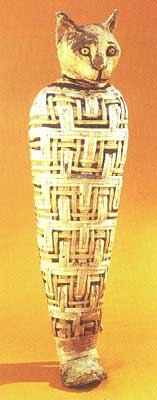

Two cat mummies from c. 332-330 B.C. in the British Museum. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

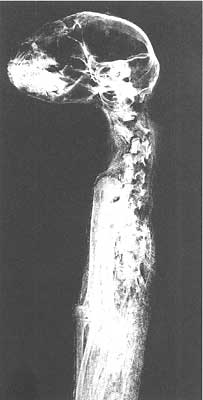

X-ray of a cat mummy showing the dislocated cervical vertebrae which

probably caused the animal’s death. The Natural History Museum,

London. |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|