|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Hippocrates

and Humoral Pathology:

The scientific study of medicine began with the ancient

Greeks who rejected the notion of a supernatural cause of disease.

Hippocrates (460-370 B.C.) is

traditionally honoured as the father of medicine. He taught his students

to carefully examine patients, classify their disorders, provide a prognosis,

implement therapy and closely observe the response to therapy. He also

emphasised the need for ethics in the practice of medicine (hence, the

Hippocratic Oath).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Roman copy of a Greek bust thought to represent Hippocrates.

Found in a physician’s tomb in the necropolis of Isola Sacra near

ancient Ostia in 1940.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

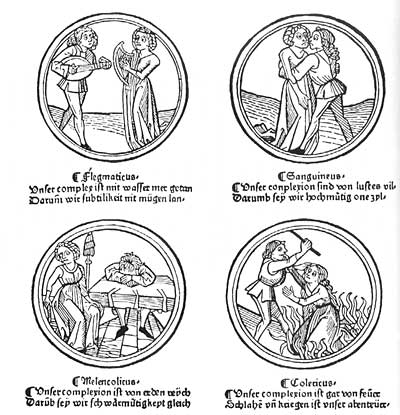

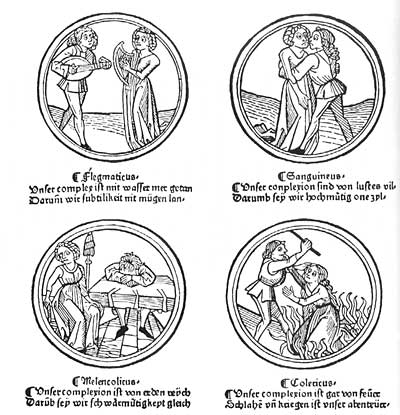

The Hippocratic

school developed the theory of humoral pathology which dominated medicine

until the Renaissance and beyond.

Extrapolating from the four elements of Greek philosophy

(air, fire, water and earth), four humours (fluids) of the body were proposed:

blood - warm and

moist (akin to air) - produced by the heart

phlegm (fibrin) -

cold and moist (akin to water) - produced by the brain

yellow bile - warm

and dry (akin to fire) - produced by the liver

black bile - cold

and dry (akin to earth) - produced by the spleen

Health (or eucrasia, Greek eu = well, krasis = mixing)

resulted from a normal mixture of the four humours. Disease (or dyscrasia,

Greek dys = bad) was due to an abnormal mixture of the fluids.

The theory of humoral pathology is still apparent in the following terms

used to describe personality and behaviour:

sanguine/sanguineous - ruddy or florid

(complexion), ardent, confident, full-blooded,

blood-stained

phlegmatic - cold and sluggish, not

easily excited

choleric (or bilious)

- angry, bitter, ill-humoured, passionate

melancholic - depressed, dejected,

pensive, miserable, mournful

Sanguineous dyscrasias were common in the spring, phlegmatic in the winter,

choleric in the summer and melancholic in the autumn. Excesses of black

bile were the most feared.

The four temperaments derived from humoral pathology,

illustrated in a German calendar, c. 1480 A.D.

The Hippocratic school correctly recognised that blood

was essential to life and that death resulted from exsanguination.

The ancient Greek physicians also observed that disease

was often characterised by fever and fluid discharges, eg. perspiration,

vomiting, diarrhoea, sneezing, and that blood clotting could be abnormal

in diseased patients.

They left good descriptions of wound inflammation, malaria,

mumps, pyothorax (pus in the chest) and puerperal sepsis. They were familiar

with malignant tumours, including cervical and breast cancer in women,

and many of their terms for tumours are still used today.

However, the ancient Greeks wrongly regarded pus as merely transformed

blood, heated to the point of putrefaction. They believed that an excess

of phlegm from the brain could, in mild cases, pour from the nose (as

nasal catarrh) or if more severe be transported to other organs to produce

pneumonia (inflammation of the lungs), ascites (excess abdominal fluid)

or rectal haemorrhoids. What today is regarded as a disease effect

was regarded by the humoral pathologists as a cause.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

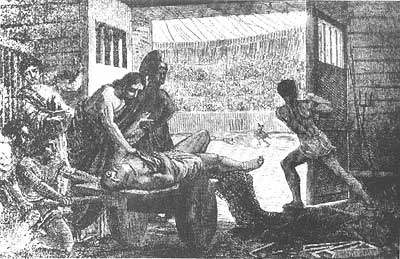

At left, Achilles treats the war wound of Telephos with scrapings from

his lance. Iron rust and bronze rust were thought to assist wound cleansing.

From a bas relief buried in 79 A.D. at Herculaneum.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

According to

humoral pathology, diseases tended to pass through three stages:

Fever and pus were manifestations of coction. Coughing,

vomiting, diarrhoea, ulceration and sweating were evidence of expulsion

of a humour.

Patients unable to achieve coction or sustain crises

could die.

The ancient Greeks cremated their dead so the Hippocratic

physicians could not perform post mortems on their patients.

Dissection of animal cadavers was common during this

period, however, and Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) made enormous advances in

comparative anatomy. One of his pupils, Ptolemy of Macedonia (a contemporary

of another pupil, Alexander the Great), founded the first university at

Alexandria and the Alexandrian Library.

For four centuries, Alexandria was the centre of excellence

in human medicine and for the first time anatomy became the cornerstone

of medicine.

According to ancient records, the early Alexandrian

anatomists dissected living criminals.

Celsus and Galen:

Most of the original records of the Alexandrian physicians

were destroyed during the military campaigns of Julius Caesar in 48 B.C.

Fortunately, much of the medical information had been

copied onto manuscripts which were exported.

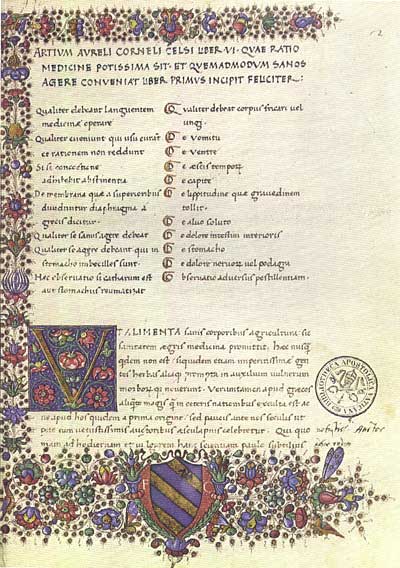

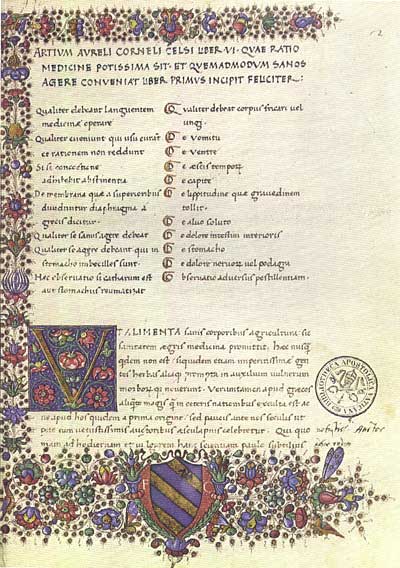

In Rome, Cornelius Celsus

(30 B.C.-38 A.D.) reproduced the essence of Alexandrian theory in his

“De Re Medicina”, an eight volume work.

Cornelius Celsus

Celsus was a Roman patrician of the time of Augustus

and Tiberius. He was not a physician but a man of leisure with an interest

in literature.

His works were ignored in his own day but were rediscovered

in the 15th century in Italy. They exerted an enormous influence on Renaissance

medicine, reinforced by the works of Galen.

A fifteenth century manuscript edition of Celsus, prepared

from the newly discovered ancient codices.

Celsus’ “De Re Medicina” contains

accurate descriptions of lobar pneumonia, appendicitis, abscessation,

gout, peripheral gangrene, gonorrhoea and urinary calculi.

In Book III, Celsus describes the classic features of inflammation:

“Notae vero inflammationis sunt quatuor, rubor et tumor,

cum calor et dolore” (redness, swelling, heat and pain).

Claudius Galen (A.D. 129-201)

of Pergamon in Asia Minor studied medicine and anatomy at Alexandria,

worked as a physician to gladiators and rose to become court physician

to Marcus Aurelius.

Galen published eighty works on medicine, anatomy, physiology and pathology.

He followed the Hippocratic doctrine of humoral pathology and his views

dominated medicine until the Renaissance.

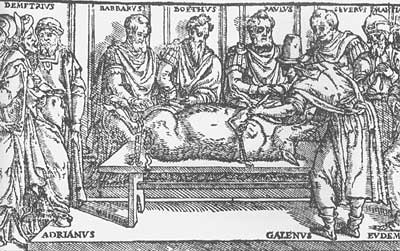

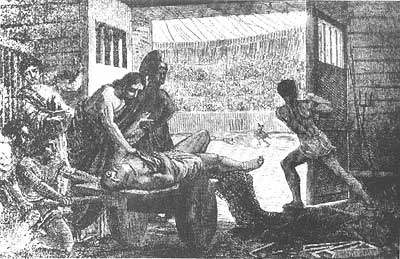

Galen

Galen treating a wounded gladiator

in the amphitheatre at Pergamon, as depicted by Jan Verhas in 1870.

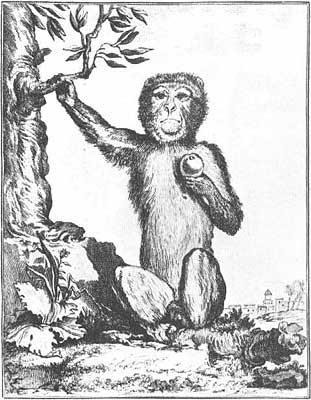

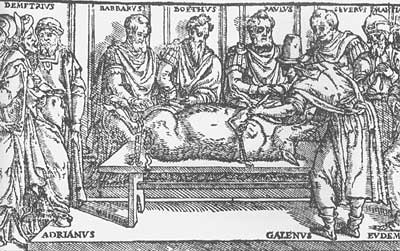

Vivisection of a pig. From a 1609

edition of Galen.

Roman law prohibited human dissection. Galen performed numerous dissections

of animals, many of them on live victims (vivisection).

He established that living arteries contained blood; he ligated the

ureters of living animals to prove that urine was produced from the kidneys;

he severed spinal cords at various levels and described the nature of

the resulting paralysis.

Galen preferred to dissect Barbary apes but, for vivisection, chose

pigs, goats or dogs.

“You avoid seeing the unpleasant expression of the ape when it

is being vivisected…the animal on which the dissection takes place

should cry out with a really loud voice, a thing which one does not find

with apes”. His text goes on to recommend that all cuts should be

performed swiftly, without pity or compassion.

His vivisection experiments demonstrated that the recurrent laryngeal

nerve controlled vocalisation.

A barbary ape (Macaca sylvanus)

Galen believed that disease was due to alteration in the humours and

that inflammation was due to a local excess of one of the body fluids.

Stagnation of a humour produced the four cardinal signs of inflammation:

redness, swelling, heat and pain; to these, he added a fifth, pulsation.

After these signs came exudation of serum and suppuration (formation

of pus).

Galen regarded suppuration (a form of coction) as an essential part

of healing. For centuries, his disciples (especially the Arabs) erroneously

went to great lengths to promote wound suppuration (hence the term “laudable

pus”).

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|