Back to Prac Classes

Modern Pathology:

Modern pathology is said to have begun with Giovanni

Battista Morgagni (1682-1771) who succeeded the illustrious

Malpighi and Antonio Maria Valsalva to the chair of anatomy at Padua.

Morgagni published records of 700 autopsies as “The Seats and Causes of Disease” in 1761. In it, he linked his patients’ symptoms to abnormalities in their organs and emphasised the importance of thorough examination and precise description of lesions.

Nevertheless, his explanations of the aetiology of lesions remained largely erroneous and based on humoral pathology.

Morgagni

Marie-Francois-Xavier Bichat (1771-1802)

identified 21 different tissues (such as nervous, muscular, vascular,

cartilaginous, osseous and glandular) within organs and observed that

disease could reflect abnormalities within these tissues rather than within

the organ as a whole.

Bichat identified the constituents of organs by dissection and by chemical analysis rather than by microscopic examination.

Bichat

The last great humoral pathologist was Carl Rokitansky (1804-1878) of the Vienna School of medicine. He explained almost all diseases as a consequence of blood anomalies.

Despite this, he was the most famous and the best descriptive pathologist of his day and he wrote the influential “Manual of Pathological Anatomy” (1846).

Rokitansky performed more than 30,000 autopsies.

His colleague was Josef Skoda, a famous clinical diagnostician who taught the Viennese medical students in the wards and whose motto was “Forget treatment; the diagnosis is everything”. In the mornings, Skoda with his students made diagnoses on the live patients. In the afternoons, the students went downstairs to watch Rokitansky perform autopsies on those who had died and to determine if Skoda had been correct.

Rokitansky

Virchow and Cellular Pathology:

Johannes Muller (1801-1858) of Bonn and Berlin was one of the first to extensively analyse biological tissues under the microscope. He laid the foundations of cellular pathology and inspired such pupils as Scwann, Henle and Virchow.

“Cell Pathology” (1855) by Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902) revolutionised the study of pathology.

Virchow emphasised that all disease is a consequence of cellular disease.

Rudolf Virchow

Virchow discovered myelin and leukaemia. He established the principles

of hypertrophy, hyperplasia, metaplasia, thrombosis, infarction, tumour

growth and routes of tumour spread and the basics of acute and chronic

inflammation.

He also forecast the development of clinical pathology.

He nevertheless remained sceptical of the role of micro-organisms in the aetiology of disease, despite the advances of Jenner, Lister, Pasteur, Koch, Klebs and others in bacteriology.

Virchow became a liberal member of the German Reichstag. He liked to describe the body as a republic in which every cell is equal.

He was loathed by the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck who once challenged him to a duel. Virchow accepted and chose as the weapons two sausages. He stipulated that his own was to be a clean cooked sausage whilst Bismarck’s was to be loaded with Trichinella larvae, served raw and eaten.

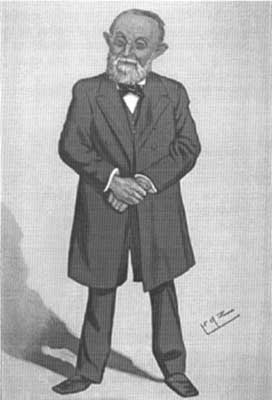

A contemporary cartoon of Virchow.

Many of the histological techniques used today in pathology were developed in the 19th century, including frozen sections.

Ultrastructural pathology based on the study of tissues by electron microscopy began in the 1930s.

The pursuit of the molecular basis of disease did not

emerge as a discipline until the mid 20th century, with Linus Pauling’s

work on human sickle cell anaemia. Molecular pathology now dominates research

in human pathology.

References:

D. Brothwell and A.T. Sandison. “Diseases in Antiquity”. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois, 1967.

R.H. Dunlop and D.J. Williams. “Veterinary Medicine - An Illustrated History”. Mosby-Year Book, Inc., St Louis, Missouri, 1996.

E.R. Long. “A History of Pathology”. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1965.

G. Majno. “The Healing Hand - Man and Wound in the Ancient World”. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1991.

C. Roberts and K. Manchester. “The Archaeology of Disease”, 2nd ed. Sutton Publishing Ltd, Thrupp, Gloucestershire, 1995.